I’m sensing a number of things coming together, creating a new view of what’s possible and what’s changing in healthcare. I want to take a moment to present some background, then share the mind-pop that hit me yesterday while writing something. It clarified my shifting view of the role of the patient in medical research – no small subject!

Background: different views of the role of the patient

As regular readers know, patient engagement got a big boost in April 2011, when I was invited to speak at TEDx Maastricht in Holland. My talk there continues to be in the top half of most viewed TED Talks of all time – an enormous boost to any cause.

Well, it’s no accident that it happened there. Organized by my now-friend @LucienEngelen, it was the first in a series of conferences he now calls “the Future of Health,” and for him it’s all about the patients – so much so that it was the first conference I know of where the first speaker announced (a year in advance) was a patient.

That’s an unconventional way to announce a new conference in medicine – and that was two years ago. He’s so patient-centered that a year later he announced he’d no longer attend or even accept speaking invitations to conferences that don’t actively support patient participation. He announced the Patients Included badge you see above. In his TEDxMaastricht talk this year he mentioned his parents’ deaths from cancer and his thoughts about his own odds. Describing the badge, he cites leaders like Gunther Eysenbach, Denise Silber and Larry Chu whose events do include patients.

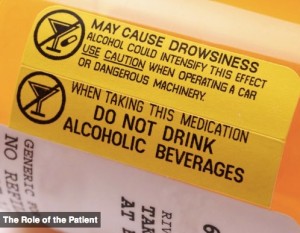

His university’s med school mission is “The patient as partner.” This touches, massively, on the TEDMED 2013 Great Challenge, Role of the Patient. TEDMED has tended to think of it in terms of whether patients follow orders: the signature graphic for this challenge (right) is a blow-up of warning labels on a pill bottle! Really, TEDMED?? This signifies the role of the patient?

And in the crowdsourced discussion, question 2 was “Is there a conflict between empowering patients and honoring the expertise and authority of medical professionals?” I have bigger possibilities in mind than whether patients heed warnings and honor authority.:-)

Taking it to the world of research

Anyway: this morning over on e-patients.net I posted about Radboud and Engelen’s latest initiative at the REshape Innovation Center (Facebook page):

The mission statement of the Radboud University Medical Center in the Netherlands is “The patient as a partner.” This month they began launching a suite of three non-profits (“a threefold rocket,” they say) where patients and their families and caregivers will come up with research ideas then try to raise the money for selected ideas.

As I worked on that post I became amazed, because I realized it put into words a concern I’ve been trying to express about PCORI, the new research agency whose work began in earnest this year. (See PCORI posts on e-patients.net.)

PCORI’s doing good things, but I realized that when they went through their process in early 2011 of defining their work, they didn’t yet have the vigorous, active patient engagement team that they have today. So in hindsight it could be said that “patient centered” was, unintentionally, defined prematurely.

Today their official definition says:

Patient-Centered Outcomes Research (PCOR) helps people and their caregivers communicate and make informed health care decisions, allowing their voices to be heard in assessing the value of health care options.

See that? It’s about developing information patients care about, on health care options that are already being developed. That’s worthy, but there’s no mention of where the options come from – how the research process is directed. It’s about a patient-centered view of the outcomes, not about patients defining the objectives of the research.

Said differently:

- The old-school approach was “We engineers [researchers] will decide what needs to be developed. We’ll let you know what we come up with.”

- Along the way, researchers led by Jack Wennberg discovered unwarranted variations in how doctors practice, and we began to develop new evidence to support doctors’ views and support patients in choosing which treatments they prefer.

- Over time, we all discovered that the outcomes that matter to scientists ain’t necessarily what matter to the patient and family.

- So, PCORI was created, to focus (see definition) on outcomes that do matter to us. The PCORI improvement is that the “engineers” of treatment [researchers and grantors] will solicit opinions from the ultimate stakeholder, as part of their process.

- But in this new Dutch approach, patient communities can come up with their own ideas, too, totally unfettered by the establishment.

And that begs a big question:

Who gets to say what’s patient-centered?

Before a big PCORI meeting this fall I blogged my current sense of the problem: Who gets to say what’s patient-centered? (Hint: the one who’s IN the center). But I didn’t yet realize where the disconnect arose from, because I wasn’t yet immersed enough in PCORI’s work to have dug back to that definition. My bad.

Before I go further, two caveats:

- I don’t speak for all patients – surely there are many who fully agree with PCORI’s definition. I’m only talking about my view.

- I’m not impugning the people who created the definition – the process was fully open and transparent, and my colleagues and I could have spoken up if (a) we’d realized the importance of the issues (which we didn’t yet) and (b) we’d realized the game was underway. But we didn’t, and I’m only now seeing why it took so long.

I imagine my friends at PCORI will point out ways that PCORI is indeed soliciting patient input on the research agenda – there was one such call for ideas this fall – but I believe those ideas get fed into the traditional process, and my instincts tell me the Dutch approach has a lot more juice to it in focusing on what patients would want if they could have anything. Time will tell – as always I’m open to discussion.

Anyway:

The Dutch article expresses what I’ve been unable to:

In my view,

- There should be an entire research agenda that’s patient-generated, without any process of submitting ideas to a non-patient board. Not everything everyone wants can be done, but efficiency will improve if patients can declare an agenda with nobody’s approval. So:

- An unfiltered, unfettered list of what patients want is a key component of any forward-thinking planning process. How else can we strive to create the most patient value for our research investment??

As the article says, the patient list is in addition to (not instead of) what the establishment is working on. (It’s just a mistake to say that all decisions should be made by well-meaning paternally protective proxies.)

To get the most for our money – and to give patients what they value most – we need to let them say it, from the outset. Anything else can’t possibly be as on-target. And that brings us to:

Rethinking who knows what’s best

In the Society for Participatory Medicine we say “patients shift from being mere passengers to responsible drivers of their care.” In the past we’ve written about going beyond “compliance,” to a vision of a future where patients design and create a safe, decent, patient-centered healthcare system. This takes it to whole different level: imagine patients directing the engineering agenda!

It reminds me of a talk by internet visionary Clay Shirky (Wikipedia) at the very first conference I ever attended, Connected Health 2008: “The patients on ACOR don’t need our permission, and they don’t need our help.” Four years later it’s encroaching on science itself.

Let Patients Help

It’s no coincidence that this leads back to the closing line of my TED Talk: “Let Patients Help” heal healthcare. One route is to re-optimize the research strategy – someday even the budget – around the ultimate stakeholder: the person and family whose lives are affected. And what I see in this initiative is a new pathway to allow organic growth of new research projects, in a new space, in addition to current methods.

So, there are a bunch of issues you touch on here. The first one is, “What is medical research and how can patients be involved?”

Medical research falls in two categories, that we can roughly categorize as biology and care models. These can be alternatively characterized as discovery research versus optimization.

Think of optimization as using what we previously discovered better. Now, discovery research is really done by biologists, not physicians. They take us from a concept to a drug without ever involving either patients or physicians. Often, the concept comes from a lucky hit or an idea based on chemistry (i.e., open calcium channels lead to oxidative stress in cells, what happens if we block calcium channels?), and the symptomatic benefit is not known until we get to human or animal studies. In this phase of research, what is important is that the chemistry makes sense, that the drugs are designed so that they pass through the appropriate membranes and not through the inappropriate ones, etc. I’m not sure that patients have a role in this, do you?

Then we get to the clinical trials. Clinical trials are primarily designed based on two factors: what has to be shown and how many people have to be in the trial for the anticipated effect to be demonstrated.

Phase 1 trials are about safety and tolerability. There’s clearly a role for patients in defining these terms, but then for power calculations (i.e., how many people need to be recruited into the study) it’s best if we define safety and tolerability based on definitions that have been used in the past.

In phase 2 and 3 trials, I can definitely see patients being involved in the design of efficacy measures, and they should be — does it make sense to test against placebo (easy) or something approaching consensus best care (harder)? There are issues in both of these, and I’m not sure that a lay collaborator (as distinct from patient who happens to have expertise — we should not use “lay” and “patient” as synonyms) could contribute meaningfully to that discussion.

Placebo controlled trials identify things that work (usually) but they don’t show that it’s better than existing standards. However, maybe something that works would work better in combination with other drugs, but you don’t want to test that in your first trial? These are tough issues, and involve both economics and science.

What we don’t want to see is a lot of trials based around “CGI” — clinician global impression of change. This is the most un-patient centric scale.

All this is just on the biology side. I could keep going into the optimization studies, which are my own primary interest… but are often overlooked and under-valued by the scientific community.

As someone who helps design studies and a patient myself, I’m interested in engaging patients in studies. However, it’s not always obvious how I am supposed to engage patients, or what level of engagement is sufficient. I’ve seen cases where a patient or two are in the room when a bunch of MDs and PhDs talk in jargon, and that’s not good, and I’ve also seen cases where patients advocate for an experimental design which would result in a multi-million dollar study that proves nothing.

I’m sold on the notion of engagement, but I’m struggling with whether I am doing enough and how to do good science in a more democratic model.

Great insight Pete into the challenges we gave in medical research and the new paradigm provided by patient empowerment and ubiquitous communication. There is a need for basic biological research, but the real opportunity is in the optimization of available solutions to improve quality access and costs for a better healthcare system. Up till recently the patient played a minor role in such research, we gathered data on them but little from them. We also concentrated on what we thought to be important, rather than what the patient saw as important.

Evidence Based Medicine was a good start on developing a better system, now we need to incorporate patient feedback and big data tools to enable us to develop a better personalized experience. However we need to keep the human touch as well. Very challenging for all of us, but I am confident it is a challenge we can meet head on in 2013.

Fabulous response, Pete! I took the liberty of breaking it up into shorter paragraphs, simply because it makes it easier for me to latch onto the individual thoughts. I’m getting lazy that way.:)

Your personal experience with these questions is invaluable, and obviously your awareness is more granular than mine (until now).

Did you read the precursor post about the Dutch experiment on e-patients.net? What do you think about situations where patients, in addition to wanting basic science, want researchers to develop new knowledge about how to LIVE WITH a disease? It intrigues me that patient-sourced ideas, vetted by an advisory panel, can then be floated to a research community to see if any researcher’s interested. I would hope that process would let interesting AND FEASIBLE ideas percolate up and perhaps get done.

Mind you, I expect challenges along the way, but I wonder what you think about the idea.

btw, A related post is going live tomorrow morning on e-patients.net from Danny van Leeuwen, a Boston-based member of PCORI’s patient engagement workgroup. Independently he came to similar ideas a month ago.

Thank you Dave. I will now have another avenue to try my ideas out on. The stroke associations are completely doctor centered. Dean

I’ll read the Dutch post later, but a quick reaction. What you call “how to live with a disease” could be pretty much the same as what I call “care models”/”optimization”: how can we apply our knowledge of biology in better ways in and out of the clinic. That’s the area where I am expert but most people are relatively uninterested — they want “cures.”

One of the studies I am doing now is: How does medication complexity affect patient- and caregiver-reported outcomes in Parkinson’s? Can we get the same clinically-measured results by using a simpler medication regimen and have a positive impact on quality of life? On the other side, “coping” can also mean palliation — making people more comfortable without necessarily making them healthier. (We tend to equate “palliative care” with end-of-life, but, strictly speaking, it’s a broader subject.) Besides things like pain relief and tremor abatement, this can get pretty deeply into areas where science (at least the kind I do) doesn’t really make sense: people should share strategies and talk about what is important to them, but I’m not sure we should measure it and say, “Watching football makes the average American male adult 10% better off than watching baseball,” or things like that.

Two small thoughts Dave:

1. I haven’t perused all the TEDMED challenges but my sense is a void of patient representation on the challenge panels. Funny; I had expected more participatoryness.

2. Stephen Jenkison of Canada’s Orphan Wisdom, in a plenary to Compassion & Choices, stated that putting the patient at the center of dying is actually a wrong move; that death ought to be at the center of dying. In his hour talk there wasn’t enough time to elaborate (he mentioned doing a workshop immediately after the plenary; too bad C&C didn’t video that, too!); he has a deep and unique cosmology around end of life matters. I am eager to learn more about it. And I thought I was contrarian.

Yes, Bart, there are fairly few “just a patient” representatives in the TEDMED challenges, and as I’ve blogged many times, it was apparent to me that TEDMED is pretty much a business conference, all about the business of medicine. After all, the Great Challenges program didn’t include a peep about the COST of care – and if that’s not one of the Great Challenges, I don’t know what is. Same for inequities – the vast differences between what some Americans get for care and what others get.

BUT that’s changing! Their graphic for Role of the Patient on the Great Challenges pageused to be a pill bottle with warnings(!) and they changed it to a handshake … in conversation with e-patients!

Re death and dying, I have nothing to add – I don’t know a lot about that field, not compared to you!