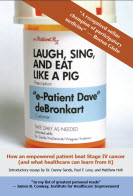

My book Laugh, Sing, and Eat Like a Pig: How an Empowered Patient Beat Stage IV Cancer (and what healthcare can learn from it) is nearing completion: it’ll be on Amazon in a week or two.

We who’ve worked on it hope it will provoke thought about how healthcare is changing because of what e-patients can contribute, empowered as individuals and enabled by the internet. To start that process, we’re publishing the introduction.

Three friends and mentors generously offered introductory essays.

These essays they have little to do with my story, and everything to do with how e-patients can help heal healthcare:

- Part 1, by Dr. Danny Sands: Putting Information—and Knowledge—in Patients’ Hands

- Part 2, by Paul Levy: Yes, Patients Can Help Their Doctors

- Part 3, by Matthew Holt: Changing Relationships and Changing Technology

Other resources: the book’s home page; previews of advance praise from reviewers

Putting Information—

and Knowledge—in Patients’ Hands

By Daniel Z. Sands, MD, MPH

My primary care physician since 2003.

The first doctor to support me in being empowered and engaged

“Knowledge is Power,” wrote Francis Bacon. Nowhere is that more true than in healthcare. Knowledge allows us to care for and advocate for our health most effectively. This is especially true in chronic and serious illness.

It is said that information is a prerequisite for knowledge (and knowledge, combined with insight and experience, can lead to wisdom), and yet physicians often avoid sharing information with patients. This information asymmetry causes patients to be deprived of the tools they need to care for themselves.

Why the reason for this asymmetry? Physicians and patients have historically played roles, with the physician as oracle of knowledge and high priest and the patient as helpless supplicant, desperately appealing to the physician for help in channeling a cure to the patient. Many (perhaps most) physicians cling to that model in some form. They are comfortable in the role as the expert, enjoy the power that comes with knowledge, and are therefore hesitant to share information with patients. Moreover, they often bristle when patients take it upon themselves to learn about their conditions, or ask about things they have read online or in the popular media. And heaven forbid they want to review their own medical records!

In defense of physicians, they spent many years in study and forced learning of facts. Sharing this information without appropriate context not only devalues their hard work but, may mislead the patient. Moreover, as physician reimbursement is ever declining, time spent educating patients—which is not generally reimbursed—is time taken away from generating revenue. Whatever the reasons, it is often difficult for patients to find physicians with whom they can partner in a mutually respectful and meaningful way, which includes full information sharing.

While this model may have been appropriate in the pre-scientific era of medicine, it no longer serves us well. We know that knowledgeable, engaged patients can more effectively care for themselves and partner with their physicians, leading to better health outcomes, more efficient healthcare, and improved satisfaction for all involved.

What are types of information that can help patients? They fall into three classes based on their availability to patients. Each patient is already an expert on certain types of information, such as about their own bodies, living situation, and how they manage their health today. Others, such as information about specific diseases or the latest medical literature, were previously the tightly guarded domain of physicians, but are newly available to everyone thanks to the democratizing effect of the Internet. The last bastion of restricted information has been—ironically—information about what lies in that patient’s own medical record.

Enlightened health care institutions, including Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, where Dave gets his care and I practice, are trying to make all information available to patients. This institution has a long history of putting patients first, including promulgating one of the first Patient Bill of Rights in the 1970s. We and other like-minded believe that informed patients make better healthcare decisions and are better partners in their healthcare. In 2000 we were one of the first US medical centers to make patients’ records available online through PatientSite, which Dave used to obtain his personal health information. I believe that all patients should have the right to view their medical records online whenever they wish.

But even with this information, it must be transformed into knowledge for it to be powerful. Physicians, nurses, and health educators can help with this, but patients increasingly help each other, through online communities. In these communities, such as ACOR (which Dave used on my recommendation), have mature and robust communities that help countless patients and caregivers with various forms of cancer. All patients facing serious illness should avail themselves of these communities.

So we see how information is increasingly available, and how it can be transformed into knowledge. This should result, as Francis Bacon wrote, in power. However, the real power in the physician-patient relationship comes from both parties sharing information and ideas freely, in an engaged, participatory, and mutually respectful environment. Both the patient and the physician benefit from this, and this power is greater than the power that each participant had on his own.

Daniel Z. Sands, MD, MPH

Senior Medical Informatics Director,

Cisco Internet Business Solutions Group

Attending Physician,

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

Assistant Clinical Professor of Medicine,

Harvard Medical School

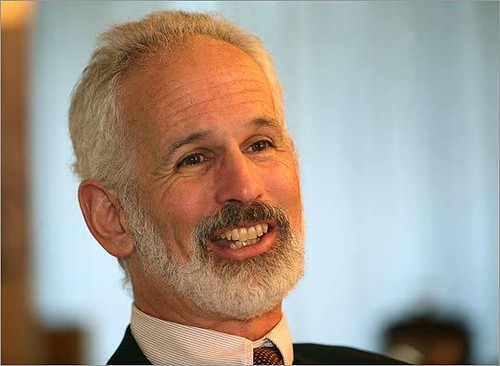

Yes, Patients Can Help Their Doctors

By Paul F. Levy

President and CEO

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

In early January, 2002, Dave deBronkart called to tell me he had stage four renal cancer, and that his life expectancy was 5.5 months. I was chairing our MIT ’72 class reunion that year. I said, “Dave that doesn’t work. We need you at the event in June.”

A little bad humor was all I could offer at that moment. Later, I found that my hospital, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, could offer much more. We had advanced treatments for Dave’s disease. As explained in his story here, those treatments worked very well. He not only made it to the class reunion, but he is still around to write this book.

But the treatment is not the real theme of the book. The theme is the journey of patient empowerment that Dave led for his own sake. And the real story is what Dave taught our doctors and nurses, and what he is now helping to teach the entire country, as he has become one of the nation’s leaders in this arena.

The standard view of the medical profession with regard to patient involvement in managing their illness is that “an informed patient will be more compliant with the regimens we say are necessary.” In other words, the information goes in one direction: We are the experts. We’ll answer your questions. But we are the experts.

I suppose we could spend a long time discussing the sociological reasons for this view. Medical people have always been highly revered in society. They go through intense technical training and have a broad scientific understanding of the human body and its diseases. They are trained, too, to be decisive, using the evidence at hand to make clinical decisions in real time. They are told that part of their job is to not make mistakes and that they have ultimate responsibility for the welfare of their patients.

Given this background, how would we ever expect a doctor to expect that a patient has something to offer in determining the path for clinical treatment of a complex disease like cancer, or even simpler medical problems?

But the truth is that the patients can bring a lot to the party. Let’s explore why. First, an MDs knowledge of any given disease is incomplete. With the rapid pace of medical discovery, it is virtually impossible for a doctor to be up to date with everything going on. Second, we need to admit that doctors generally do not practice evidence-based medicine. Experts like Intermountain Health’s Brent James have pointed out the high degree in variability with which virtually identical patients are treated. He uses terms like “regional medical mythology” in describing this lack of standardization.

But there is another factor to consider as well. Even if doctors can keep up with the latest scientific information and even if they assiduously try to apply it, the degree of variability among patients themselves makes it difficult to assume that the general statistics (think 5.5 months) apply to the particular case. Any probability distribution is, in fact, a distribution with tails (aka “outliers.”) One that is based on a relatively small number of cases is particularly subject to wide standard deviations. One that is based on emerging treatment technologies and approaches is even more subject to a lack of specificity. In short, a problem in medicine is that a statistic often gives the impression of precision when precision is lacking.

In this situation, there is another source of information for the doctor, someone who has an intense vested interest in success – the patient. Now, let’s admit that Dave was an outlier himself when it came to patient involvement. He is computer savvy and was indefatigable (yes, even with cancer) in searching out the latest about everything.

But, as I have talked with dozens of other patients, it is apparent that they spend a lot of time exploring the web, participating in support groups, and talking with friends and families about their medical situations. When I have talked with doctors here, they are replete with stories about how a patient has helped them resolve difficult treatment decisions. Sometimes this happens because of technical information provided by patients. Often, though, it is because the patient has “inside” information about his or her own body that puts the doctor’s technical knowledge into a more immediate and precise context.

Dave’s story offers a dramatic exposition of the advances in cancer treatment that can turn an acutely fatal outcome into a long life. His more important story is how doctors and a patient working in partnership can learn from one another. His plan is to shift the balance of power in clinical settings into a true balance of power, one based on mutual knowledge, respect, and empathy.

I, for one, am glad that he was able to attend that reunion.

Paul F. Levy

President and CEO

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

Boston, MA

May 2010

Changing Relationships and Changing Technology

Founder, The Health Care Blog

There’s a lot that’s unusual about Dave’s story – today. The interesting question is, what will make the best parts of this story commonplace?

There are two factors. One’s moving along fast, another isn’t.

The first is a key change in the doctor-patient relationship: participation. The easier availability of more information gives patients a chance to work better with their physicians – to be better educated, which lets the physician have a better time of it. Patients can have a better understanding of what their role is in their outcome. Dave got it in part by other patients helping to target his search; others are getting it from tracking their own personal health information. In any case patients today can know a lot more than a generation ago. And it’s already much easier than when Dave was sick in 2007. This part is moving fast.

The second factor is coming, but not as fast as it should: better connectivity. Dave had online messaging with his physician, and someday everyone will, with better record keeping as part of it. For the same reason better coordination between physicians is coming. Most records are still on paper, and tests get redone needlessly, but we’re starting to see sharing of tests, images and more getting easier for clinicians.

It’s not here yet but we can taste the fact that better information for the physician and the patient makes getting to the right decision easier.

I’m honored and humbled that these three thinkers find the book’s message worth their time to share their thoughts. I hope you’ll find the book worth your time, too: my story is just one example of what’s happening everywhere as patients and clinicians begin partnering in participatory medicine.

To be notified when the book is available for order, send email.

I agree with Matthew about the slow evolution of patient/physician communication. When I want to contact my pain-management specialist, I have to get past the walls his staff holds up around him, first. On the phone, I have to leave a message with the nurse. If she can’t help and I don’t want to set an appointment, then I can leave a message for the PA. Under no circumstances have I ever heard the physician’s voice on the phone. Nor will he answer his own e-mails or provide an IM address. I get the same kind of response from my pulmonologist and my ENT.

Understand, I’m very picky. I won’t work with a doctor who withholds information, pooh-poohs my research, or otherwise attempts to treat me like a child. My docs are über-competent men and women who collaborate with me on my medical care–except with regard to 21st Century communications. Austin is supposed to be a high-tech locus, yet every medico in the area seems to work behind the same kind of communication walls. We need to break out of this 20th Century communication ghetto and introduce Austin HealthCare to Web 2.0.

Hi Dave,

Don’t want to overstay my welcome at this site, but I posted the earlier comment in response to Matthew’s post, and I hadn’t yet read the other two. After reading Dr. Sands’s and Dr. Levy’s posts, I find that something about participatory medicine is nibbling at my spine. For once, I think it’s more than my own degenerating discs.

Like many other empowered patients on the web, e-Patient Dave’s is a fascinating tale of survival. That seems to be the prerequisite to getting a doctor’s attention in terms of participatory medicine. As I noted in my review of Matthew’s section of the introduction, my luck with doctors has been a bit less participatory. I’ve yet to find a doctor who would answer emails. In fact, only one doctor of mine ever shared an email address, and he never answered it, just his receptionist (mostly to say, “the doctor will have to address those issues during your next visit.”)

So, I have to ask the good doctors, is a death sentence a prerequisite to direct communication? I’m a 51-year-old man with a few health problems. So far, none of them are life-threatening. My spine is degenerating. I have asthma and seasonal allergies. I’m beginning to think I might have an enlarged prostate. Does one of these problems have to become a cancer before a doctor will answer my emails? I realize that doctors work long hours, and I know that most doctors still get paid only for piecework. Visits generate income. Emails just take time. Still, do I really need to visit my pulmonologist every time my scrips run out? Do I really need to sit in the office with my pain specialist every time I need another epidural injection? All I do in those visits is answer a few questions. Isn’t that time better spent with people who really require an exam? Is this a situation we can change?

BillDog, will you shut UP :–) about overstaying your welcome?? Just put that crap out of your mind (and keep it out of my ears).

In my experience there’s no correlation between openness and proximity to death. I’ve heard tales of people near death who were stiffed by providers, and that really scrapes me the wrong way. In one case an in-law was left to die in a room by the doctor – they didn’t even try to feed him, and when his family complained they said the family would need to realize that this was the end. Family instead helicoptered him to a better hospital, and he died 20 years later – 10 years after the doc who’d left him to die.

I am not you, so I don’t know what you want to do, nor what your options are. If I were in your shoes I’d ask my insurance company what my options are for finding a doctor who will welcome my participation, my help. They may say “Have at it – here’s our online [or paper] directory – go for it.” Or not.

First step in empowerment is to realize you’re allowed to ask for what you want. I think you passed that state long ago. Second step is to do the asking, and if you don’t get it, keep looking.

Don’t get me wrong, this is new stuff for a lot of communities – sorta like when women in the 60s started asking for equal opportunity. Some people rebel against such change: my high school’s athletic director quit when the law was passed that said girls should have a sports budget too.

Keep in touch. You’re a live specimen of this change. There’s no roadmap – we’re makin’ it up as we go along.

(Any other advice, anyone?)

There is a fourth kind of information not mentioned here, and it is the most important kind. You cannot get it from anyone in medicine. They don’t have it themselves. They won’t record it. They don’t believe the patient community is smart enough to interpret it. And they are really worried that it might ruffle some caregiver’s career . . . What is the success rate of the caregiver and the institution? What is the infection rate? What is the crime rate in the facility? Only 2% of adverse events are accurately reported. The most important information patients could have is lost in the other 98%. How empowered can a patient be when a patient cannot even learn if the caregiver being recommended injures more people than he/she saves but always creates a record that shows the opposite? That caregiver’s colleagues won’t even report it when the caregiver practices under the influence or simply is so incompetent nurses steer patients around him/her when possible. Until that fourth kind of information is available, the rest is only marginally better than nothing.

Hi Joel – nice to see you here.

As it happens, all of the people who contributed to this introduction are actively involved in working toward better healthcare. In particular Paul Levy’s hospital openly posts its error rates, on its website, and he blogs frequently about the measures they’re taking to reduce errors.

I could say a lot more but I’ll just say that important subject isn’t in these essays because this book is my cancer story, not a book about all the many important issues in patients getting engaged in their care. That would be a very big book.

Mine does cite Trisha Torrey’s excellent You bet Your Life: 10 Mistakes Every Patient Makes. You’ll also be heartened by The Empowered Patient, due out in a month, from Elizabeth Cohen, which talks a lot about wising up, as does Trisha’s.

Thanks Dave for bringing these three great together to write a wonderful introduction to your book. In the cancer community that I moderate, I witness patient peers encouraging one another to be participatory in their care and to acknowledge that they are the experts of themselves.

I welcome the day when people like you, Trish, Elizabeth and so many others have revolutionized the attitudes of medical professionals to the point that they will in turn encourage patients to be participatory and help patients acknowledge that they have expertise to contribute to their care.

Look at this powerful message about patient expertise strung together using quotes from Dr. Danny Sands, Paul Levy and Matthew Holt: