Let us start by reviewing our anthem: “Gimme My DaM Data – it’s all about me so it’s mine,” by the magnificent Ross Martin MD and his wife Kym, multi-cancer patient whose care has been affected by lack of access to her health data. “DaM” is Data About Me, Kym’s more-polite version of my cussing. Read on for why this is newly urgent.

As regular readers know, I’ve been having an exchange of posts (and emails) with Dr. John Halamka, the Chief Information Officer of my hospital, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), which wonderfully saved my life in 2007.

John and I differ profoundly in our opinions about whether patients should have the ability to download every bit of their medical record, including the ability to take it wherever we please and share it with other hospitals and apps. If Kym had had this ability years ago, her care would have been better informed.

Differences of opinion are okay, but the latest is that he’s pretty much refusing to answer my concerns, instead putting up an almost Trump-like diversionary wall, changing the subject and not answering the question.

John, my concern here is not for myself – I’m healthy right now. My concern is for patients and families (like Kym, not long ago) who have active problems right now and whose ability to get the best possible care is impeded by your beliefs and policies. On what moral grounds do you deny them access?

I’ll start with a brief recap, for newcomers, then give my objections to your latest non-answer, and repeat my questions – actually, I’m ready to call it non-negotiable demands.

Brief recap (let’s call it “history of present illness”):

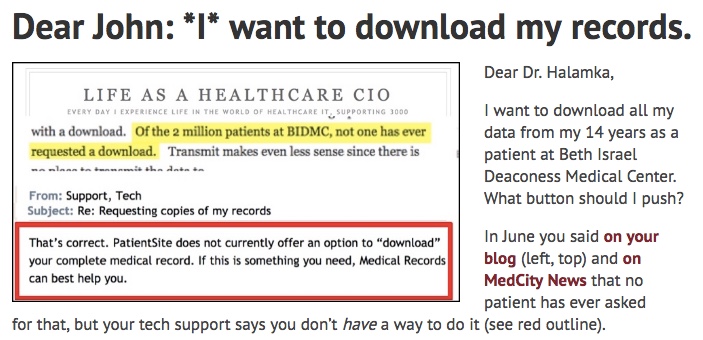

- June 2016: John blogged that “not one [patient] has ever requested a download” [at BIDMC] and cross-posted a version on MedCity News.

- Several friends on social media who know PatientSite (BIDMC’s patient portal), wrote privately to me saying this made their blood boil because it was so disingenuous. Read on, for why.

November 7: I replied *I* want to download my record, but that his own tech support told me they don’t have a way to do it! (Graphic, right)

November 7: I replied *I* want to download my record, but that his own tech support told me they don’t have a way to do it! (Graphic, right)

- They said I’d have to talk to Medical Records, which told me they don’t have the ability to deliver electronically!

- November 9: he replied in a post mysteriously titled What is patient and family engagement? – “mysteriously” because it doesn’t answer the question, and because it again doesn’t respond to my request.

My response:

John and I have known each other since before our 2009 dust-up about Google Health, when the BIDMC interface to Google sent garbage, not my clinical data. (More on this is in my “I want to download” post above.) He is a master (which I respect as a professional skill) of emerging from any accident landing on his feet and lookin’ and smellin’ great. :-) But that doesn’t solve any patient’s problem. Sidestepping political problems is a skill, but it doesn’t help patients sidestep risks and impediments.

Reader, if you haven’t read John’s Nov. 9 post, I ask that you do so. If I’m misreading it, say so in comments. And I know John will correct anything he’s I’ve missed. [Typo fixed.]

- First, let’s stick to my original question: Where is the link you say nobody has ever used?? Your June post used that as an argument to say Meaningful Use was premature, but that’s bogus: you don’t have the link you say nobody has used.

- If you don’t have one, your assertion implodes and you have no case. You must concede, or rebuild your argument without that bogus sentence.

- Worse, as my wife said in 2009 and I said recently, you belittle patients by saying we don’t want what many of us are in fact asking for. (In 2009 you said insurance billing records were “confusing” to consumers, when in fact the picture they gave me in Google Health was false. For instance, you sent them “Metastases to the brain or spine” when I in fact did not have that; nor did I have non-rheumatoid tricuspid valve disease, though BIDMC mysteriously billed them for it; nor did I have an aortic aneurysm (that was “upcoding”); etc.)

- You say “patients typically do not want raw data, they want something actionable – the tools necessary to assist their navigation through the healthcare process.”

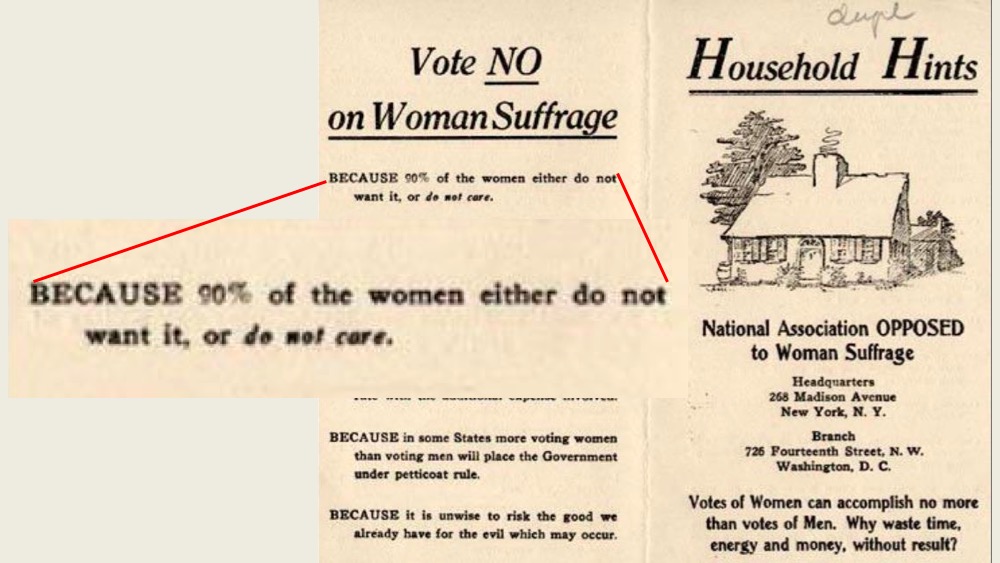

What does your view of “patients typically” have to do with we who do want our raw data?? That’s exactly like the 1912 election flyer that said to vote no on women’s suffrage because 90% of women aren’t asking for it. (Right??)

What does your view of “patients typically” have to do with we who do want our raw data?? That’s exactly like the 1912 election flyer that said to vote no on women’s suffrage because 90% of women aren’t asking for it. (Right??)- Let me refer you to this 2009 Tim Berners-Lee TED Talk, which ends with him urging the audience to chant “Raw data now!” (I know … what does the inventor of the Web know about data, compared to doctors, right?)

- Most important: how does your interpretation help a family with a serious problem that does want their raw data, to understand the case or seek help from other providers? Do you feel you have a right to impede this?

- You said, mostly correctly: “we do not know precisely what patients want. It would be hubris for any IT leader to speak for all patients. We need to try many different technologies and let the patients decide.”

- But I’d go an important step further: Give us our data, and let many innovators innovate for us. We do not want you to decide what you think will work best for us!

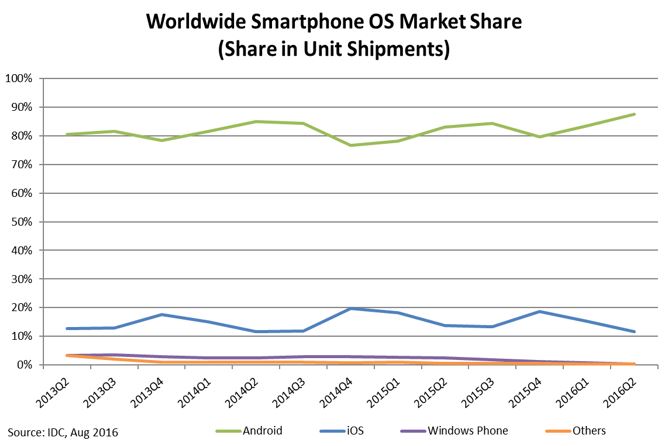

iOS is a minority of the citizen user base. Surely you know this.

John, you say you’re developing an iOS-based solution, which will offer users the data you believe they need. I have two problems with this.

- Who are you to decide? That’s what’s known as paternalism: “You don’t know what’s best – I do. I’ll decide for you.” What about patients with real medical problems, whose needs are different from your middle?

- iOS is a small share of what people actually have. Everyone else’s needs are in no way served by an iOS solution.

Here, look – IDC’s August post on the subject, with the chart at right. “Android dominated the market with an 87.6% share in 2016Q2. … iOS saw its market share for 2016Q2 decline by 21%.”

Here, look – IDC’s August post on the subject, with the chart at right. “Android dominated the market with an 87.6% share in 2016Q2. … iOS saw its market share for 2016Q2 decline by 21%.”

Don’t like that graphic? Google it yourself for more – iOS android market share.

Edit: below, commenter John Grohol points out that these are global numbers and we should focus on US market share, since Meaningful Use is a US policy issue and John’s BIDMC app will only apply to the US, where iOS share is 40%.

On the other hand, I’ve heard in numerous countries that the same debate exists, so I guess it’s worth noting both numbers.

I know you love Apple – me too: my family has 2 Macs, 2 iPhones, 2 iPads. It’s fine with me if you develop iOS tools that will totally kick butt. But that doesn’t help the majority of patients with medical problems. They will still need their data.

So while you work on iOS, my original need still stands: Give us our data. All our data.

Your turn. Please change your policy. No, not “please.” This has become a non-negotiable demand. I say your policy is impeding best possible care.

Develop the world’s greatest iOS tool, if you want. Meanwhile, GIVE US ALL OUR DATA. Who are you to say paternalistically that we don’t know what’s best for us?

I am shocked to hear Halamka claims that patient’s don’t want their data, and with that raw error, self-created, then refuse to make access to those that do request it. It is the absolute right for every patient to have access to all their data, what ever form it takes. Of course, one must simply assume that if the hospital or medical system cannot supply that data immediately to the patient, then it cannot supply that data to the patient’s doctor!

Having one’s own data–to use, to share, or NOT to use or share–is the right of the patient. It is not to be impeded in any way, nor is there any value in doing so, except to those who wish to disempower both patients, and dare I say it again, other physicians.

In my role as a patient advocate, I have just heard of the ‘loss’ of many records earlier than 2009 as requested by patients at Cleveland Clinic. This is blamed on their electronic system. I cannot verify this, but patients who wish to understand their initial cancer diagnosis, to compare tumor growth or such are unable to do so.

I refuse to repeat that mealy-mouthed phrase, “This is unacceptable”. Instead, we all need to say very clearly, “This is wrong, and will not stand”.

> Instead, we all need to say “This is wrong”

That’s not too dissimilar from the 2009 Google Health adventure, in which Dr. H said “We now understand that claims data is confusing to consumers,” when the reality was that the claims data produced a wrong medical record.

Yes, this is wrong, and should be stopped.

I’m guessing one problem is the severely mistaken mooshing-together of “most patients I’ve seen” into “therefore all patients, ever.”

I think it’s highly disingenuous for anyone to say they *never* had anyone do XYZ. Of course they have had people ask for their data. Just because this individual doesn’t know about it doesn’t mean it hasn’t happened. For instance, does the Medical Records department at BIDMC actually track how many patients ask for their electronic medical records? (If they don’t, well, that’s the problem right there).

Second, according to sources (https://dazeinfo.com/2014/10/20/apple-inc-aapl-samsung-005935-smartphone-market-us-growth-q3-2014/ ), iOS is probably about 40% of market share in the U.S. (compared to Android’s 52% or more). Now, while that’s still a minority and significantly so, we should only be looking at the U.S. (since we’re talking about U.S. healthcare here, primarily). Sometimes developers or companies make the decision to develop first for iOS because of specific considerations (it’s easier/cheaper, accessible development staff experience, etc.). It doesn’t excuse NOT addressing/developing for Android or, you know, the Internet as a web-interface (and possible API). But it might help explain it a bit…

It’s definitely an odd decision I don’t agree with, nor do I agree that no patient has ever asked for the electronic medical record at BIDMC. Of course they have. Saying otherwise is just plain denial (whether conscious or because the data capture abilities there are inadequate).

Thank you, John – your perspective is always sober and much valued. I’m adding your US share note to the post!

Strongly agree that patients have more than a right to every bit of data about themselves – – it’s a need, and we need it NOW – – as without all the data about your own body, you are crippled in both understanding your own situation and in seeking second opinions or any other further medical advice.

Patients who feel immortal or overwhelmed by medical matters and aren’t yet asking for downloads need their data, too, because the day will come that they’ll need to show their medical records to a doctor they don’t know, or who doesn’t know all about them, and hope that the information is complete enough and accurate enough to get them the best possible treatment.

Truly, we shouldn’t even have to ask for our medical records. They should automatically follow us around, with patients controlling who sees them, with a process for patients, caregivers and medical professionals to flag errors for routine correction.

For those who still need convincing: let’s imagine the roof on your house needs fixing or replacing, but you don’t know how big your roof is, what kind of materials were used, method of installation, warranty, tax rebates, etc., etc., and must rely on information available only to roofers. How can you possibly evaluate bids and negotiate for what you want while talking to local roofers? Would you really want them to decide what’s best for you?

As for Android vs iOS, I am astounded every time I hear people make comments assuming that the world revolves around Apple. Effective design considers how people really live/choose and want to live/choose, rather than how the designer feels they “should” live. So Android, as the world’s current overwhelming first choice, should be first when designing for the public. For marketing reasons, it probably makes sense to launch new apps with rollout on at least the top two platforms – since iOS includes a lot of early adopters whose enthusiasm can be useful.

Great piece in an ongoing saga of what is becoming mythic proportions.

I wonder about the potential benefit of using SoMe to make this keep appearing in John Halamka’s circles?

Upton Sinclair said: “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it!” [ https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Upton_Sinclair ] John is still the premier spokesperson for a hospital-centered health IT architecture and it’s difficult to expect him to adopt a patient’s perspective as long as that’s the role he chooses in the national conversation.

The salary issue is easy to understand if you see the hospital institution as a rent seeking-intermediary in a healthcare business where the the global corporation produces, the licensed physician prescribes, and the patient consumes. These are the three principals in a US system that already costs 30% more than other developed economies – with no end in sight. Compared to the three principals, the hospital is just another data broker extracting value – and John’s salary – as middlemen. As networking and computation get cheaper and more reliable, the value of hospital based systems and other data brokers diminishes and the pressure to dis-intermediate them grows. It would be amazing indeed if John were to prove Sinclair wrong by setting an example in support of patient-centered health records.

Though you both have the same objective of optimum health for everyone (or in this analogy the perfect dish), you want to be given the raw data (raw ingredients) and achieve optimum health (cook the dish) according to your idea of what optimum health is (according to your taste), or at least have the option of bringing these raw data to another doctor (chef) of your choice; while John, being a master chef, prefers to cook the dish according to the cooking world’s standards using the raw ingredients given him by the hungry patient. John prefers to use the oven of his choice (iOS) while other ovens may be used and still come up with the perfect dish.

My question is why can’t both be done—give the raw and analyzed data to the patient, and let him decide what to do next? He can eat up what is given him or have it cooked in a way more to his liking.

> why can’t both be done

Precisely – as I said, go ahead and create the most awesome iOS app (“meal”) in the world. But:

a. If I want something not on the menu, for heaven’s sake don’t tell me to go without; and,

b. For heaven’s sake, don’t leave all the non-iOS people starving

And for heaven’s sake don’t intentionally block other chefs from feeding people by keeping the ingredients from them!

Gimme My DaM Data! Give all of us our damn data. It ours to do with it what we want. Mayo gave me mine … so what did this grad from the Google School of Medicine do with it? I seized my opportunity in this digital age of information … hacked the on-line mutation data banks … targeted the suspected gene culprit … cracked my genetic code and made a significant genetic discovery which was recently published in the peer reviewed Journal of Cardiac Electrophysiology.

JCE’s Editor and Chief had this to say to me: “You should feel good about your role in this for it may save lives and/or ameliorate suffering … this is priceless.”

Take note Dr. John Halamka, “the future of medicine is not going to be the exclusive purview of medical professionals … Our best hope for the future lies in connecting the most motivated parties (the patient) with data and tools that allow them to explore and learn — to give power to the people”.

Harnessing the power of MY genetic information and invoking the ancient wisdom of Hippocrates: “Let food be thy medicine” … I not only attenuated, but reversed my cardiac instability and walked again. I did this after being diagnosed with 2 seemingly unrelated rare diseases and being told I was likely to drop dead of sudden cardiac death and that I was likely to lose my ability to walk … there was nothing I could do about it … I had to accept my genetic fate … but I didn’t. I seized my data and went deep … deeper than any of my Mayo docs could possibly afford … but they co-authored my case report with me. We E-patients are the future.

My favorite article about my genetic discovery:

Power to the People

Posted On 20 Aug 2014 By Knox Carey In Biology, Ethics, Technology:

An inspiring article in Ars Technica describes the case of Kim Goodsell, an endurance athlete who discovered a novel genetic flaw linking her two rare diseases, Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC). Kim spent hundreds of hours teaching herself genetics, enough to read and make use of the extensive research literature at Pub Med. She combed through 40 different genes believed to play a role in her disease, finally homing in on LMNA, which codes for a protein integral to the structure of the envelope around the cell nucleus.

To verify this hypothesis, Kim asked for a complete sequencing of her LMNA gene, at personal cost, and against the advice of her doctors. How did doctors respond to her request?

But as it turns out, Kim was correct — she had an extremely rare mutation in a highly-conserved locus of LMNA. Subsequent academic research corroborated Kim’s unpublished result about the connection between LMNA, Charcot-Marie-Tooth, and ARVC. Although her conditions are (currently) incurable, Kim is taking scientifically informed measures to manage her conditions.

I think this case teaches several valuable lessons:

——Patients are highly motivated, and will go to great lengths to understand their diseases. They have a much greater incentive to spend time and effort on research than any doctor, and we in healthcare must do everything that we can to empower them in their efforts. Anyone with a hypothesis should be able to test that hypothesis, no matter how outlandish or non-intuitive. That is how new discoveries are made.

——Data and tools need to be available to the general public. We are still in the early days of genomic medicine, but genetic data will be collected in increasing volumes and those data need to be accessible to patients. Patients and other non-professionals need to have access to tools that help them make sense of their data. In Kim’s case, a very simple program could have flagged her rare variant as a “variation of unknown significance”. A community of Kims would be even more powerful, allow a researcher (academic or otherwise) to look for correlations between genotypes and phenotypes. I believe we are seeing just the beginning of the potential for crowd-sourced research.

——As more data come online, we need to understand the ethical and privacy requirements for genomic data, and design systems (like Genecloud) that take these factors into account. We must always keep in mind that governance cannot come at the expense of access and utility — we need to remove obstacles to research, not erect new ones. Balancing these concerns is of the utmost importance.

As I think Kim’s case illustrates, the future of medicine is not going to be the exclusive purview of medical professionals, nor is it solely in the hands of those who can bring the greatest computing power to bear. Our best hope for the future lies in connecting the most motivated parties with data and tools that allow them to explore and learn — to give power to the people. —Knox Carey

Ubiquitous connectivity, the online democratization of information, social media, the fury of hyper-innovative digital technology and consumer genomic sequencing have precipitated a radical shift in the power and organizational structure of medicine. This confluence of technologies have spawned “the digital patient revolution”.

Genius is our innate birthright; mediocrity has been imposed. Digital technology is serving to engage and unleash the element of “genius” in the population at large. It’s time to raise patient expectations in both the patient and the healthcare community to enable patient participation in the co-production of medical intelligence.

Our biggest obstacle in the face of the conventional paternal patient/doctor relationship is to pierce the barrier of disbelief – the belief that patients are not capable of directing their medical healthcare.

Once this barrier is broken we will race into a Golden Age of collaborative healthcare.

Phenomenal note, Kim! Congratulations on the recent coverage of your achievements!

For those who don’t know, Kim Goodsell (@KimGoodsellRova) is the big featured e-patient story at the start of The Patient Will See You Now, the 2014 book by famed cardiologist and geneticist @EricTopol. (For the hundreds of articles about them, from MedScape to National Geographic, see this Google search.)

Consider this, from the book’s review in the NY Times Sunday Book Review, by cardiologist Sandeep Jauhar:

“For too long, health care has been stymied by paternalistic restrictions on patient involvement. At some level this is because of information asymmetry: Doctors are privy to much more medical knowledge than their patients.”

Note, this was in a review that did not entirely agree with the book!

Nobody’s saying this transition will be smooth: Kim notes that at Mayo they did give her all her data, even though at least one physician was skeptical. I think that’s good – in times of change caution and earnest skepticism are appropriate. But for heaven’s sake let’s not willfully hold back patients’ ability to help their own (or their families’) causes!

As more stories like this accumulate, I have to wonder: will Beth Israel Deaconess want to become known in the media as being less progressive than Mayo?

As I follow this discussion I keep wondering about the decision making structure in this and other healthcare organizations. Why does one person have the ability to make this decision? It is a power struggle. Not only with patients; providers in this system are trying to provide patient centered care while dealing with this type of leadership. Restricted ability to collaborate with patients. We need to address this from a safety and quality perspective.

I take your point about this being an intra-US debate, but ‘the DaM data’ question is global* — so your point about iOS-myopic developers ignoring the addition (which should be their priority, really) of Android to roll-outs as a ‘bare minimum’ requirement really is a issue of worldwide significance.

Keep on beating this drum with the biggest sticks available until everyone gets the rhythm.

Email subscriber Andrew10 sent this comment, which I’m posting here with permission:

I agree with you I should be able to see my records and download them. I feel I should be able to add to my records .

Here is the reason I feel I should be able to add to my records I recentlly started to have chest pains. I ended up in the emergency room; the information the ER had was outdated

I had more problems/ I ended up in a urgicare center; they had no records of my problems . ( the doctors in my area are slow to use electronic records )

I finally got to see my family doctor. My doctor told me it is usually a three to five day wait for records from other facilities .If I had been able to access my records and update my records I could have saved my self a lot of trouble and expensive tests and lost wages, I took off from work for these appointments.

I am a physician from India and after reading this thread I want to take up a position on this highly debated topic of “spigot like access” of patient data to the Patient.

I am a doctor and “was declared” a patient as well.

I’m a country like India, Medical Spigot is a necessity. I cannot comment on US healthcare system as I am not a part of it.

India has highly disorganised healthcare system. A country where doctors are considered as incarnation of God’s. The arrogance, high handedness of many doctors are in the news now and then. It’s only Patient Data ( not the Patient generated data ) which can put the accountability to an otherwise unregulated healthcare system.

My story and experiences have been horrible and car acrid to,be shared in an open forum, but if I see the big picture probably I would favour taking a small risk and allow patient complete access to his data, rather than to permit unethical, clandestine and surreptitious malpractice even if practiced by a handful number of professionals.

Two things:

– in jurisdictions that have PHI access laws, in most cases, hospitals cannot rely on the “we don’t know how” to provide an exception to access. That get-out-of-jail-free-card, by itself, is not enough. Give me my data, please.

– In jurisdictions like Ontario, Canada, and others, the provider must, by law, state any gaps known in the response, if they are relevant to the known purpose of the [patient’s] request for information. Surely the existence of undisclosed raw data constitutes a gap to someone who wants “all” their records for the purpose of re-evaluating their own healthcare. Nevertheless, in my experience, providers routinely omit statements acknowledging the existence of raw data.