I’ve been writing (and speaking) about this Superpatients concept and book for more than a year, and it was stuck for the longest time as I groped for some organizing context in which to explain everything. I mean, here we have all these amazing stories of amazing people who’ve done remarkable things, with some common themes weaving in and out, but it just didn’t have any framework on which to hang those themes. And without a framework, I can’t explain anything.

Well, this week it came to me, and now the book is tumbling out of my fingers. In the same way that my prior book Let Patients Help starts with a set of Ten Fundamental Truths about Health and Care, this book needs a similar set of foundation truths. Fourteen have come out so far. Last night I started creating memes for them, and it’s time to start pushing them out, one a day for two weeks.

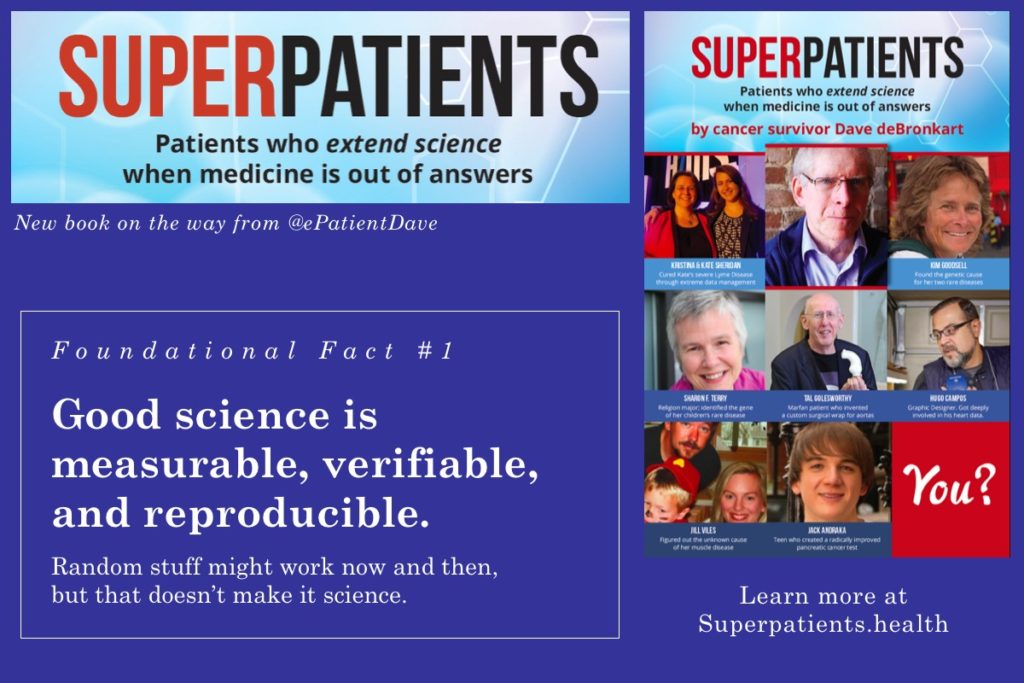

So today I tweeted this:

Well okay, the book tweeted it. And here’s the first of those tips, and its meme:

“Good science is measurable, verifiable, and reproducible.”

Why is something this obvious a big deal? Well, it turns out not everybody knows this – not even everyone in healthcare. Or they know it and keep forgetting. And it turns out you really need to understand this if you want to innovate in a way that’s going to work reliably.

But you also need to understand it if you’re going to question the establishment – or question innovators. A hallmark of bad science is that it works sometimes but at other times doesn’t. As the meme says, “Random stuff might work now and then, but that doesn’t make it science.” To the contrary, that’s exactly why people believed in witchcraft before science: they saw something happen once (“That woman with a black cat visited just before my wife died!”) and made up an explanation … which, it turned out, did not hold true the next time a woman with a black cat visited.

Importantly, that principle applies just as well to science that’s published in medical journals: an alarming amount of it is bad science. And as we’ll see in an upcoming episode, it’s really important to understand that if you want to extend medicine’s frontier.

The very essence of science is to answer the question, “What advice can we count on?” Stay tuned.

Next in the series: #2: Not all published science is good science.

Summary of the whole series:

- #1: Good science is measurable, verifiable, and reproducible

- #2: Not all published science is good science.

- #3: Don’t expect docs to know all and others to know nothing.

- #4: Related myth: “Count on scientists to find what needs to be found.”

- #5: Some doctors were trained wrong about what information’s dependable.

- #6: There have been profound changes in what’s possible at the fringe of knowledge.

- #7: Empowerment means increasing someone’s abilities.

- #8: Paternalism is based on expired truths. Don’t let it kill you.

- #9: Scientific journals have different motivations and “biological clocks” than desperate people.

- #10: “The lethal lag time” – new knowledge doesn’t flow instantly to everywhere

- #11: Beware “eminence-based medicine.”

- #12: Not all truth has been discovered yet.

- #13: Some useful information will NEVER make it into journals.

- #14: It’s your data. Get it.

A hallmark of bad science is that it sometimes works and sometimes doesn’t–the results are not reliably repeatable. Yes. And you make the point that an alarming amount of the science published in places like medical journals is exactly this kind of bad science. Also yes.

However, I would point out that in the field of medicine, a lot of what is solidly good science is nevertheless not 100% always certain. It’s a matter of probabilities–not usually iron-clad certainties. Repeated experimental evidence may show us that X does work, or Y does not work…but for some patients here and there, X simply does not work even though it should, or Y does work, even though it defies “logic” to understand why.

That was one of the things that swayed me to the side of conventional medicine (vs. alternative medicine) when I was diagnosed with cancer. The alt-med “cures” always spoke in terms of 100%s. They were portrayed as cures for all types of cancer, all stages of cancer, etc. Meanwhile, articles I was struggling to read in medical journals were a bit more circumspect, pointing out that this chemo regimen produced a certain length of response in certain kinds of cancers or cancer patients with certain distinct profiles–seldom did conventional medicine approaches make claims to be a cure-all. The ability to speak in terms of likelihoods impressed me.

However, while there are swaths of modern medicine that do speak in terms of probabilities, there are also vast swaths of the field that do not use that language to any appreciable extent–especially when speaking to patients. They speak in totalizing statements, because what they are talking about is true 95% of the time. So they fail to even NOTICE that 5% of the time, it is not true, and they fail to consider (too often) that the patient they have before them just MIGHT be one of that 5%.

Just because a given bit of science is measurable, verifiable and reproducible doesn’t mean it’s 100% true all the time, for all people, in all settings….

You are, not surprisingly, right on track and already in front, right where things are going :-). Thanks!

I want to note here that not all useful information exists as “measurable, verifiable, reproducible” experimental evidence. That’s especially true when you’re at the frontier of knowledge.

Later principles touch on different parts of this.