After my previous post Winter’s coming. Time to talk about ventilation for coronavirus defense I’ve been amazed that hardly any businesses I’ve visited are using HEPA filters – or if they are, they’re not touting it. Why??

This is important information, with potentially huge benefits for businesses and customers alike. Why are we all focused on waiting for treatment, when all of us (anywhere on the political spectrum) want two things:

- Be safe

- Get back to “as normal as possible” as fast as possible.

I have a relative whose school is thinking seriously about this subject, so I’m going to do several follow-up posts based on feedback I got from the previous post.

- This one’s about the difference between “droplets” and “aerosols” – a source of much confusion, I’ve found – and how masks block their nasty travels.

- The next will be about other brands of home & office room-air HEPA filters besides the one we bought

- A third will talk more about the science of aerosols. Nobody doubts that big sneezed droplets can infect people, but there’s lots of disagreement about whether aerosols can. I found someone whose academic career was in studying aerosols; the reason for the uncertainty is frankly bothersome: no funding to study the key issue.

First, clarity: let’s call aerosols “mists.”

A constant point of confusion is the difference between “droplets” (bigger drops coming out of your face) and “aerosols” (smaller ones).

I finally figured out that “mists” is a much less confusing word.

Droplets fall to the ground.

Aerosols don’t. They hang in the air. Like a mist.

Now: How filters work against mists

In my previous post I quoted this, from the May Consumer Reports article on HEPA filters:

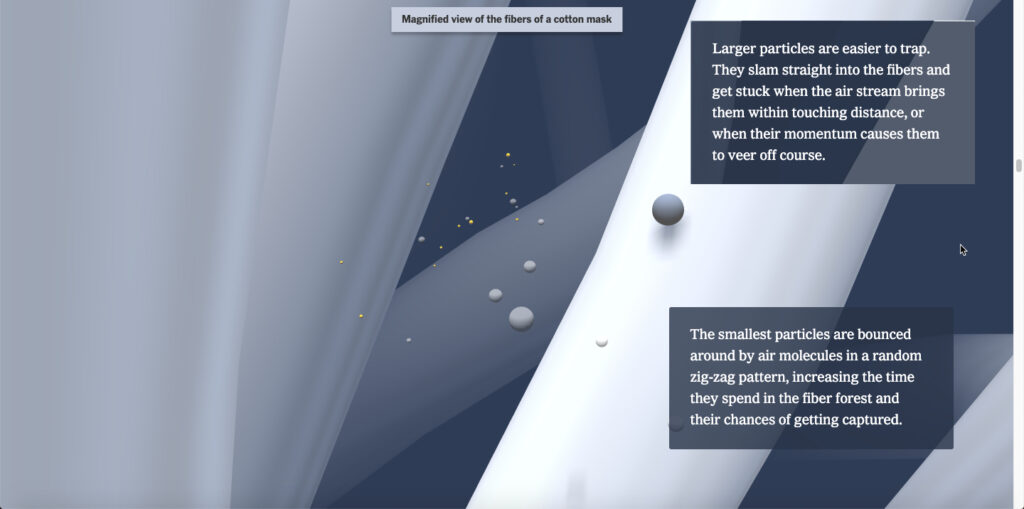

HEPA filters are very effective, certified to capture 99.97 percent of particles that are precisely 0.3 micron in diameter. (Particles that size are perfectly suited to maneuver through the filter’s fibers, while larger and smaller particles, because of the various ways they move in the air, crash into the structure.)

Intellectually I could understand that but honestly I had no gut feel. Then last Friday the New York Times published this gorgeous animation of how particles float through the air and get caught by the fibers in a mask. Please click that and spend a few minutes scrolling through – that’s all it takes.

I hope the link in these tweets will work. Email subscribers, you may need to click the headline to come online and see it. A twelve second excerpt from the full animation is in the second tweet shown here:

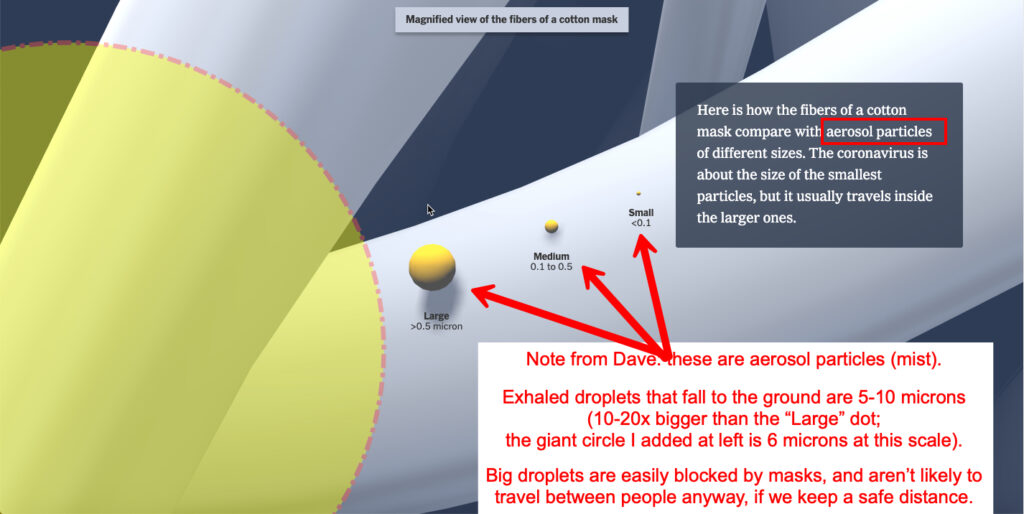

I’ve screen-grabbed a couple of moments to make my point, and to encourage you to look at that link (here it is again). First, here’s an extreme blow-up of what it’s like inside a typical cotton mask as mists float through. The biggest yellow dot is half a micron, which is 140x skinnier than an average human hair:

(As the tweet says, “If you were the size of an aerosol particle, you might have to wade through more than a mile of this fiber forest to get to the other side.”)

To add some context, I marked this up a bit. The big yellow circle I added is about 6 microns, in the size range of ordinary droplets we exhale in talking or singing or heavy breathing, which can carry a killer amount of virus particles:

Still, that big blob’s wicked tiny – six times smaller than the eye can see (40 microns).

Finally, here’s a composite of a couple of later “scenes” in the animation as it follows some of these buggers on their weaving path, surfing the airstream as you breathe in or out:

Aha! The animation helps me understand at last that Consumer Reports phrase that says “larger and smaller particles, because of the various ways they move in the air, crash into the structure.”

And that sets the stage for discussion of HEPA filters – because holy cow, if a thing I can buy at Home Depot can remove nearly all those things from the air in a room – perhaps ten times an hour – then holy cow, I can start to understand how I’m trying to keep myself safe. Even if it’s not appearing on TV or in news articles. (Why not???)

Remember: nothing is certain, but prevention makes sense.

Note: I said reduce infections, not absolutely prevent. I’m so sad to see people on Facebook share stories of “Masks don’t work! My grandfather used one and he got the virus!” Nothing in prevention is absolutely certain, people. (Some people in seat belts still die, but far fewer than before. Some people on birth control get pregnant, but far fewer. Some people who brush teeth get cavities. Etc.) Everything we do in prevention is to reduce and manage risks.

That’s what you want to do, right?? Reduce your risk of getting this virus? And America’s risk, and the world’s?

In the absence of finished science, we’ve got to keep asking ourselves: How much can we understand so far, and what steps can we take that make sense? My standard advice has been:

- Keep your distance whenever possible.

- When close to others, wear masks. They block freakin’ droplets (and mists). (Now you understand that more.)

- Wash and sanitize when exposed to contact risks.

- Avoid dangerous people, the same as you avoid dangerous drivers.

To this I’m now adding, as winter arrives:

- Avoid unfiltered air when indoors with others.

The next post will be more about that. Because it’s all a lot better if we can just filter those buggers out of the air, which strongly makes the work of masks that much easier.

Action:

Why are restaurants and shops and schools not talking LOUDLY about this, and displaying their in-room HEPA filters for all to see, and why are we not asking them all “Do you have HEPA filters?” Let’s do it!

From Angie Claussen on Facebook: (She contributed some links in my previous post)

Nice essay!

The other point here is that reducing the amount of virus exchanged between 2 masked people, through distance and 2x 2 layers of cotton, isn’t the end of the probability game.

Virus getting through a mask isn’t like sperm getting through a hole in a condom. It doesn’t just take one to make things happen – there is indication that being exposed to a low viral load means increased likelihood your body can fend the virus off without it even taking hold, even if small numbers of virus get through. After all, household transmission is somewhere around 30-50%. Some people in some circumstances can fend off virus without getting sick or it even taking hold (my daughter’s college roommate got sick and my daughter tested negative twice through swabs and has no antibodies despite sharing a tiny room for the 3-4 infectious days, there must have been some virus in the air, but not enough).

Masks help in keeping that viral load small enough amounts to fend off infection.

In addition, there is some information that being exposed to a high viral load means you are more likely to get really sick, so persistent mask wearing may decrease the likelihood of hospitalization and death, even if it results in transmission. (The roommate wore her masks religiously except in the shower and had a mild case, so while that doesn’t prove anything, it fits the expected pattern).

And it seems not to be directly linear – there is some form of threshold involved in viral load at exposure, and viral load at becoming critical.

So masks add to the probability of 4 different measures of infectiousness staying under a critical threshold.

– do I expel enough virus towards you that it can reach you?

– do I expel enough virus towards you to make it past your mask to get into your lungs?

– does enough of the virus get in your lungs to stick around and not get destroyed off the bat?

– does enough of the virus get in your lungs and body to overwhelm your immune system?

Consistent mask wearing gets you more rolls of the dice in your favor. I’ll happily add those to distance and ventilation and staying away from people who don’t follow advice and don’t understand probability.

https://www.statnews.com/2020/04/14/how-much-of-the-coronavirus-does-it-take-to-make-you-sick/

Angie, that’s such a great comment that I might make it into a post of its own!

German friend Astrid Schott says “This is the great scientific summary about aerosol distribution of covid19” – a google doc from several scientists

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1fB5pysccOHvxphpTmCG_TGdytavMmc1cUumn8m0pwzo/edit

I’ll be sharing this post. FYI…I got a LEVOIT filter (2 actually). They are significantly quieter that the Honeywell that I returned.

Never knew of this brand but glad that I did.

Thanks, DK! Please share – why did you folks pick that brand, and for that matter, why did you decide to get one? For increased safety during family visits? Other?

What model?