In August Medical Futurist Bertalan Meskó and I published Patient Design: The Importance of Including Patients in Designing Health Care in JMIR, in the Journal of Medical Internet Research (JMIR). It ties together aspects of both our work. He’s a medical futurist, less than half my age, with a clear vision of how medicine will work in a future unencumbered by today’s limits. For me, an advocate for patient empowerment, it’s rooted in patients having the power to get the care they want. Our views come together in the idea of patients designing the care they want. From our abstract:

… genuinely empowered people living their lives and managing their health according to their own priorities, in partnership and consultation with physicians as needed.

The paper is discussed in more depth on the SPM blog: Patient Design: The Importance of Including Patients in Designing Health Care. Here, I want to tie it to a specific example I witnessed a lifetime ago. I wasn’t one of the changemakers myself but I sure saw it going on around me, and I learned plenty from women whose views were changing.

The Boston Women’s Health Collective

I was a college student in Boston during the Vietnam War, with all its cultural upheaval, which continued after the Vietnam and Nixon years. We were all learning to ask, about everything in life, “Wait a minute – whose idea was this??” and ask if this was really what we wanted. At an individual level, nowhere was this more apparent than in women’s health, which led to my own early awakening about health and care, when the Boston Women’s Health Collective started calling on us all to wake up and think about whether we were getting what we wanted.

Consider this incident reported by a woman named Miriam Hawley, who I met in 2018. From 1966:

“What’s in this pill?” I asked the doctor. He came over and patted the top of my head and said, “Dear, dear, you don’t have to worry about it.”

… I wanted to understand what he was recommending for my body and why. He thought that was silly. And I got angry.

Three years later she was among the founders of the Boston Women’s Health Collective, a group who met in 1969 to talk about what they wanted and why they weren’t getting it.

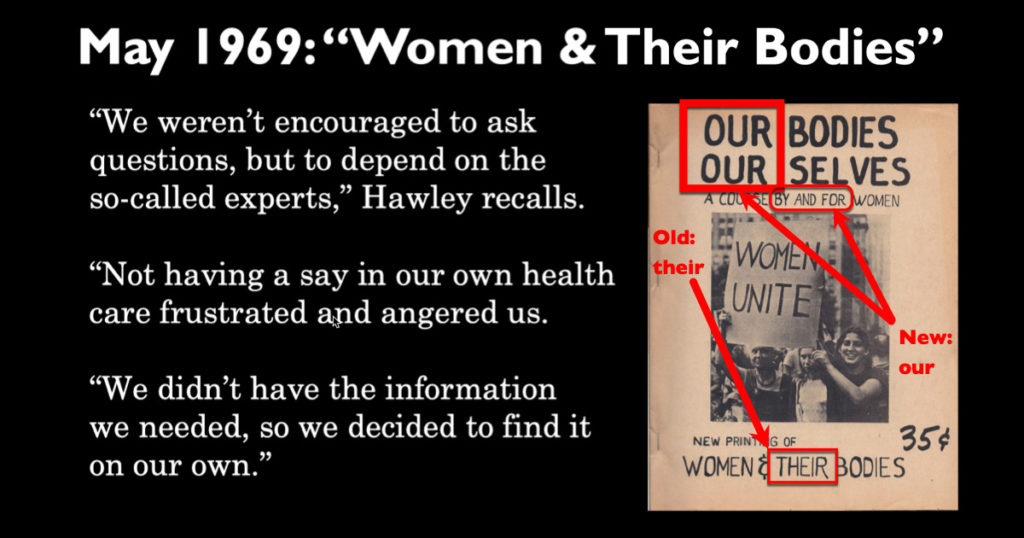

Recalling those times, Hawley later told a reporter, “We weren’t encouraged to ask questions, but to depend on the so-called experts. Not having a say in our own health care frustrated and angered us. We didn’t have the information we needed, so we decided to find it on our own.”

That’s the very picture of empowerment. Let’s unpack it:

- “Not having a say in our health care”: they knew what they wanted, which is the first step in being empowered, and they asked for it. They were told no.

- “Frustrated and angered us”: when their requests were denied, they were self-aware enough to identify their feelings, so they could consider what to do about it. Specifically:

- “We didn’t have the information we needed”: they realized their problem and named it. So:

- “We decided to find it on our own”: instead of saying the powerless “There’s nothing we can do about it,” they took action.

In short, the establishment wasn’t delivering, so they took matters into their own hands.

They gathered information, assembled it, and published it in a form their peers could use. It became the now-classic book Our Bodies, Ourselves, which today has millions of copies and excerpts in 33 languages. For more on what a turning point that book was, see the WBUR post that I co-wrote with Hawley at the 50th anniversary. It was a thrill to meet her – see photo!)

“You don’t have to worry about it,” said the old-fashioned paternal doc. “We wanted to worry about it,” said the empowered woman Miriam.

“When someone else speaks for you, you lose”

I cited that classic line on the e-patient blog: “When someone else speaks for you, you lose”: patient empowerment as a civil rights movement. When you wake up and realize what you want, and realize others aren’t delivering it for you, you have a choice: do you settle for what you can get (we all do that sometimes), or do you decide to speak up and say “We’re not getting the care we want,” as the Boston Women’s Health Collective did a half century ago?

Today you and I today have far greater access than ever to knowledge and to tools. Indeed, in the era of social media, the OpenAPS Type 1 diabetes community tweeted #WeAreNotWaiting and eventually created a whole new self-made and self-managed way to control their blood sugar. We could easily say they morphed “By and for women” into “By and for people with diabetes.

The best possible future of care – “best possible” as defined by the people with needs, the patients – will be when patients are genuinely involved in designing the care they want and need.

Leave a Reply