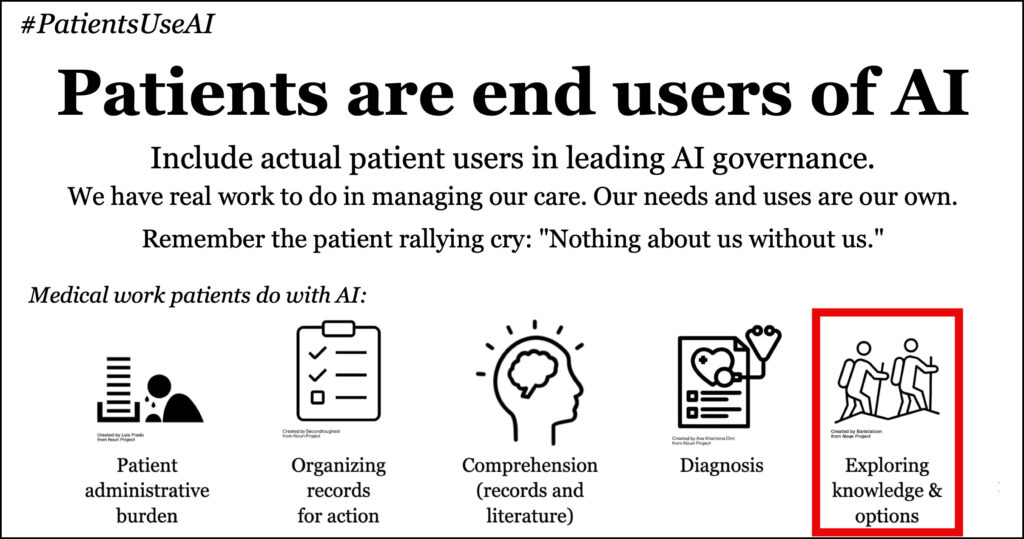

Next in the series about the new hashtag #PatientsUseAI. It’s important that medicine know this, because our priorities can be different from the industry’s, and we need this powerful tool too.

My first post said that while the world rushes to regulate AI, healthcare is ignoring patients as actual users of the technology. And that’s a huge oversight that we must fix.

Patients have real work to do.

AI can help do it.

The graphic above listed five categories of patient work. The next post in the series was the first: coping with a difficult diagnosis. It spoke of how the great physician Eric Topol included two such patient stories in his recent TED Talk. (See photo, and the caption of what he said!)

When a doc like that makes a point of including two patients as successful users of AI, you know #PatientsUseAI for real.

Next up: exploring knowledge & options

Today’s “patient use case” is so spectacular that it was featured in the inaugural issue of the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine‘s new AI journal. In her new column, journalist Carey Goldberg fantasized about a thoroughly modern hospital that might invite their patients to use AI, even putting ideas in their head. And one idea was the famous e-patient Hugo Campos, who has a potentially lethal heart condition: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). Our Hugo, in NEJM!

Last summer at the time I talked to him, everyone was worrying that AI can hallucinate, so patients might naively ask it a question, get a wrong answer, and hurt themselves. Hugo laughed and replied, “Dave, I don’t ask it for answers – I use it to help me think.”

See, every patient with HCM is different in their heart’s details, so it’s essential to him that he think things out, and that he understand as much as he can about new medications, for his time-limited doctor visits. (His cardiologist loves how engaged he is.) As Carey writes, “he had extended conversations with both GPT-4 and Claude.ai to analyze the pros and cons of using one blood pressure medication rather than another in a detailed analysis that a doctor likely did not have time for.” (An example of one nerdy prompt he used: “Please compare the inotropic and chronotropic effects of verapamil and diltiazem on the human heart.”)

Note the important point: you can spend as much time as you want talking with your AI. You can ask it to clarify, you can ask for more details, you can take it on a tangent, without worrying that you’re “wasting the doctor’s time” or annoying anyone..

She also cited my friend “DJ” (not his real name), who has seriously unstable blood pressure. He “wanted to try a wearable all-day blood pressure monitor (ABPM) and used AI to marshal the arguments to persuade his doctor that it made sense — and succeeded.” At bottom of this post I’ll paste in the specific prompt he gave GPT-4 – it’s impressive, and it proves that nobody should decide for patients what they think patients will be able to do.

Note that in both cases the patient used AI to be more prepared and informed for their next doctor visit. To be a more effective partner in the care relationship.

And that brings up perhaps the most important point about this. As Hugo was describing his new freedom to explore a topic endlessly, he laughed out loud and said:

“At last: autonomy!”

When kids grow up and get liberated and become adults, they become autonomous and can pursue whatever they want, as far as they want. Of course we have to teach them how to not drive like idiots, how to handle money, etc … and I strongly believe we should teach everyone how to use AI safely and successfully.

And that in turn is a further reason to realize: #PatientsUseAI.

In the next posts we’ll get into the other patient uses we’ve identified so far: Comprehending medical material, Organizing documents and records, and Patient Administrative Burden.

DJ’s prompt about ABPM

As noted above, DJ taught himself some pretty slick stuff by experimenting with GPT-4. (He hasn’t used others yet.) Here’s how he asked it to dig up the information he needed to prepare for a conversation with the doctor. I’m including this here to illustrate how sophisticated a person with no medical training can be, when motivated.

Note that, like many of us with a chronic condition, he’s learned the lingo. He composed this in Word, then pasted it in.

Patient, male, age 75, non-smoker, average weight, recent diagnosis of moderate aortic calcification, no history of MI’s, previous diagnosis of premature ventricular events, well controlled type 2 diabetes with an A1c of 7±, and labile hypertension. Patient has history of three orthostatic hypotensive falls, but none since on his current meds, which have been reduced in strength.

Patient is also under the care of a cardiologist, who prescribed his current hypertension meds, however, his associate physician’s assistant that he’s seen was unfamiliar with the existence nor benefits of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring until brought to her attention by my patient. Patient also has been recently diagnosed via sonography for venous insufficiency in the left leg from the knee to the ankle, contributing to intermittent foot and ankle edema.

No evidence of DVT, cardiac insufficiency or other blockage was diagnosed.

Currently, morning meds prescribed by the cardiologist include 150mg metoprolol tartrate, 25mg HCTZ and 100mg losartan potassium. In the evening, the patient was prescribed and takes an additional 100mg of losartan potassium.

BP remains not properly controlled, particularly in mornings through late afternoon, approaching 160+ systolic and 80+ diastolic with a median pulse of 80.

What meds could be added or changed to achieve better control?

How can the dosing regimen and timing be modified to achieve a normalized BP average of 120/80?

Write your response at a JAMA submission level.

He also asked it for journal citations for key points, to show to his physician’s office. Because of the risk of hallucinations, he checked each reference. Then he printed it and took it to his next visit.

Super impressive! Super empowered patients!