This is the latest in the Speaker Academy series, which started here. The series is addressed to patients and advocates who basically know how to give a talk but want to make a business out of it. I’ll try to be clear to all readers, but parts may assume you’ve read earlier entries.

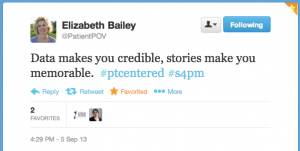

Several times a week I find myself citing this tweet, from Sept. 5. That means it’s time to blog it, so I can find it when I want to.:-)

It’s by Elizabeth Bailey @PatientPOV, author of The Patient’s Checklist.

This is vital advice for patients who have a story and want to be a memorable, effective speaker. I know you want to tell your story, partly because you want others to know what you went through, partly so they can be better prepared themselves as a patient, and often because you want to raise awareness of the issues you faced. It’s important: stories evoke emotion and lead to caring. Stories connect to the base of the brain, and can be compelling.

But although a single story can be compelling, it’s not enough to create change. A single story is called an anecdote – an isolated case – and every scientist and every policy person is trained to not build policy on a single case. A foundation for change requires larger data.

I’d never heard someone connect those dots as clearly as this tweet – and that’s why I’ve been quoting this tweet so much. In my own speeches, I tell my story, and then I back it up with data:

- “If I read two articles a day, after a year I’d be 400 years behind.”

- “The lethal lag time: research doesn’t reach doctors until 2-5 years later”

- “Zero cases of ‘death by googling’ in a three year search”

Depending on the audience I’ll then pull out other facts, but those are the core. So: the basic structure of my talks is this:

- Connect with people’s hearts with your story

- Present facts (data) that establish “It’s not just me. This is big enough to do something about.”

- Then you need to give them a clear sense that they can do something about it – it’s not hopeless.

- This is vital – people hate to feel hopeless, so you have to show them a pathway to a better future, or they’ll stop thinking about you, your story, and your data … just as surely as when you cause cognitive dissonance (Speaker Academy #4).

Future posts will get into the third one. It’s important, because while #1 and #2 create the need for change, the last thing you want to do is leave the audience just feeling bad or feeling powerless.

Thank you, Elizabeth!

Next in the series: #15: The contract